Eyes Like Sky And Coal And Moonlight Read online

Page 3

“More dangerous than any tabby cat,” Rik said.

I knew what he meant, but I kept a lightning rod at hand in the wagon seat in case of trouble. Bupus knew I’d scorch his greasy whiskers if he crossed me.

There is a tacit understanding between a Beast trainer and her charges, whether it be great cats, cunning Dragons, or apes and other man-like creatures. They know, and the trainer knows, that as long as certain lines aren’t crossed, that if expectations are met, everything will be fine and no one will get hurt.

That’s not to say I didn’t keep an eye on Bupus, watching for a certain twitch to his tail, the way one bulbous eye would go askew when anger was brewing. A Beast’s a Beast, after all, and not responsible for what they do when circumstances push them too far. Beasts still, no matter how they speak or smile or woo.

At any rate, Bupus felt obliged to maintain his reputation whenever another wagon or traveler was in earshot.

“Gnaw your bones,” he rumbled, rolling a vast oversized eyeball back at me. The woman he was trying to impress shrieked and dropped her chickens, which vanished in a white flutter among the blackberry vines and ferns that began where the road’s ground stone gave way to forest. A blue-headed jay screamed in alarm from a pine.

“Behave yourself,” I said.

He rumbled again, but nothing coherent, just a low, animal sound.

We were coming up on Piperville, which sits on a trade hub. Steel figured we’d pitch there for a week, get a little silver sparkling in our coffers, eat well a few nights.

It had been a lean winter and times were hard all over—traveling up from Ponce’s Spring, we’d found slim pickings and indifferent audiences too worried about the dust storms to pay any attention to even our best: Laxmi the elephant dancing in pink spangles to “Waltzing Genevieve,” the pyramid of crocodiles that we froze and unfroze each performance via a lens-and-clockwork basilisk, the Unicorn Maiden, and of course, my Manticore.

Rik was driving a wagon full of machinery, packed and protected from the dust with layers of waxed canvas. He pulled up near me, so we were riding in tandem for a bit. No one was coming the opposite way for now. We’d hit some road traffic coming out of Ponce’s, but now it was only occasional, a twice an hour thing at most.

“You know what I’m looking forward to?” I called over to him.

He considered. I watched him thinking in the sunlight, my broad-shouldered and beautiful husband and just the look of him, his long scholar’s nose and silky beard, made me smile.

“Beer,” he said finally. “And clean sheets. Cleeaaaan sheets.” He drawled out the last words, smiling over at me.

“A bath,” I said.

A heartfelt groan so deep it might have come from the bottom of his soul came from him. “Oh, a bath. With towels. Thick towels.”

I was equally enraptured by the thought, so much so that I didn’t notice the wheel working loose. And Bupus, concerned with looking for people to impress, didn’t warn me. With a sideways lurch, the wagon tilted, and the wheel kept going, rolling down the roadway, neat as you please, until it passed Laxmi and she put out her trunk and snagged it.

I put on my shoes and hopped down to examine the damage. Steel heard the commotion and came back from the front of the train. He rode Beulah, the big white horse that accompanies him in the ring each performance. Sometimes we laugh about how attached he is to that horse, but never where he can hear us.

The carts and caravans kept passing us. A few waved and Rik waved back. The august clowns were practicing their routine, somersaulting into the dust behind their wagon, then running to catch up with it again. Duga was practicing card tricks while his assistant drove, dividing her attention between the reins and watching him. Duga was notoriously close-mouthed about his methods; I suspected watching might be her only way to learn.

“Whaddya need?” Steel growled as he reached me.

“Looks like a linch pin fell out. Could have been a while back. Sparky’ll have a new one, I’m sure.”

His blue gaze slid skyward, sideways, anywhere to avoid meeting my eyes. “Sparky’s gone.”

It is an unfortunate fact that circuses are usually made of Family and outsiders—jossers, they call us. Steel treated Family well but was unwilling to extend that courtesy outside the circle. I’d married in, and he was forced to acknowledge me, but Sparky had been a full outsider, and Steel had made his life a misery, maintaining our cranky and antiquidated machines: the fortune teller, the tent-lifter, and Steel’s pride and joy, the spinning cups, packed now on the largest wagon and pulled by Laxmi and three oxen.

The position of circus smith had been vacant of Family for a while now, ever since Big Joy fell in love with a fire-eater and left us for the Whistling Piskie—a small, one-ring outfit that worked the coast.

So we’d lost Sparky because Steel had scrimped and shorted his wages, not to mention refusing to pay prentice fees when he wanted to take one on. More importantly, we’d lost his little traveling cart, full of tools and scrap and spare linchpins.

“So what am I going to do?” I snapped. Bupus had sat down on the road and was eying the passing caravans, more out of curiosity than hunger or desire to menace. “I’ll gnaw your bones,” he said almost conversationally, but it frightened no one in earshot. He sighed and settled his head between his paws, a green snot dribble bubbling from one kitten-sized nostril.

The Unicorn Girl pulled up her caravan. She’d been trying to repaint it the night before and bleary green and lavender paint splotched its side.

“What’s going on?’ she said loudly. “Driving badly again, Tara?”

The Unicorn Girl was one of those souls with no volume control. Sitting next to her in tavern or while driving was painful. She’d bray the same stories over and over again, and was tactless and unkind. I tried to avoid her when I could.

But, oh, she pulled them in. That long, narrow, angelic face, the pearly horn emerging from her forehead, and two lush lips, peach-ripe, set like emerging sins beneath the springs of her innocent doe-like eyes.

Even now, she looked like an angel, but I knew she was just looking for gossip, something she might be able to use to buy favor or twist like a knife when necessary.

Steel looked back and forth. “Broken wagon, Lily,” he said. “You can move along.”

She dimpled, pursing her lips at him but took up her reins. The two white mares pulling her wagon were daughters of the one he rode, twins with a bad case of the wobbles but which should be good for years more, if you ignored the faint, constant trembling of their front legs. Most people didn’t notice it.

“She needs to learn to mind her tongue,” I said.

“Rik needs to come in with us,” Steel said, ignoring my comment. “He’s the smartest, he knows how to bargain. These little towns have their own customs and laws and it’s too easy to set a foot awry and land ourselves in trouble.”

Much as I hated to admit, Steel was right. Rik is the smartest of the lot, and he knows trade law like the back of his hand.

“I’ll find someone to leave with you, and Rik will ride back with the pin, soon as he can,” Steel said.

“All right,” I said. Then, as he started to wheel Beulah around. “Someone I won’t mind, Steel. Got me?”

“Got it,” he said, and rode away.

“I don’t like leaving you,” Rik said guiltily. It was a year old story, and its once upon a time had begun on our honeymoon night, with him riding out to help with the funeral of his grandfather, who had been driven into a fatal apoplectic fit by news of Rik’s marriage to someone who’d never known circus life.

“Can’t be helped,” I said crisply. He sighed.

“Tara…”

“Can’t be helped.” I flapped an arm at him. “Go on, get along, faster you are to town, faster you’re back to me.”

He got out of his wagon long enough to kiss me and ruffle my hair.

“Not long,” he said. “I won’t be long.”

“We’

ll leave Preddi with you,” Steel said, a quarter hour after I’d watched Rik’s caravan recede into the distance. It had taken a while for the rest of the circus to pass me, wagon after wagon. Even for such a small outfit, we had a lot of wagons.

Preddi was Rik’s father, a small, stooped man given to carelessness with his dress. He was a kindly man, I think, but difficult to get to know because his deafness distanced him.

We pulled the wagon over to the side of the road, in a margined sward thick with yellow loosestrife and dandelions. A narrow deer path led through blackberry tangles and further into the pines, a stream coming through the thick pine needles to chuckle along the rocks. I tied Bupus to the wagon, and brought out a sack of hams and loaves of bread before making several trips to bring him buckets of water.

Preddi settled himself on the grass and extracted a deck of greasy cards from the front pocket of his flannel shirt. While I worked, he laid out hand after hand, playing poker with himself.

The day wore on.

And on. I cleaned the wagon tack, and repacked the bundles in it, mainly my training gear. Someone else would be tending my cages of beasts when they pitched camp, and truth be told, anyone could, but I still preferred to be the one who feed the crocodiles, for example, and watched for mouth rot or the white lesions that signal pox virus and clean their cage thoroughly enough to make sure no infection could creep in under their scales or into the tender areas around their vents.

Bupus gorged himself and then slept, but roused enough to want to play. I threw the heavy leather ball and each time his tail whipped out with frightening speed and batted it aside. Fat and lazy, he may be, but Bupus has many years left in him. They live four or five decades, and I’d raised him from the shell ten years earlier, before I’d even bought the flimsy paper ticket that led me to meet Rik.

I hadn’t known what I had at first. A sailor swapped me the egg in return for me covering his bar tab, and who knows who got the best of that bargain? I was a beast trainer for the Duke, and mainly I worked with little animals, trained squirrels and ferrets and marmosets. They juggled and danced, shot tiny plaster pistols, and engaged in duels as exquisite as any courtier’s.

The egg was bigger than my doubled fists laid knuckle and palm to knuckle and palm. It was coarse to the touch, as though threads or hairy roots had been laid over the shell and grown into it, and it was a deep yellow, the same yellow that Bupus’s eyes would open into, honey depths around clover-petaled pupils.

I kept it warm, near the hearth, but could not figure out what it might contain. Months later it hatched—lucky that I was there that day to feed the mewling, squawling hatchling chopped meat and warm milk. I wrapped the sting in padding and leather. Even then it struck out with surprising speed and strength. A Manticore is a vulnerable creature, lacking human hands to defend the softness of its face, and the sting compensates for that vulnerability.

He talked a moon, perhaps a moon and a half later. I took him with me at first, when I was training the Duke’s creatures, but a marmoset decided to investigate, and I learned then that a Manticore’s bite is a death grip, particularly with a marmoset’s delicate bones between its teeth.

Some Beast trainers dull their more intelligent Beasts. It’s an easy enough procedure, if you can drug or spell them unconscious. The knife is thin, more like a flattened awl than a blade, and you insert it at the corner of the eye, going behind the eyeball itself. Once you’ve pushed it in to the right depth, perforating the plate of the skull lying behind the eye, you swing back and forth holding it between thumb and forefinger, two cutting arcs. It bruises the eye, leaves it black and tender in the socket for days afterward, but it heals in time.

It doesn’t kill their intelligence entirely, but they become simpler. More docile, easier to manage. They don’t scheme or plot escape, and they’re less likely to lash out. Done right, even a Dragon can be made clement. And those beasts prone to over-talkativeness—dryads and mermaids, for the most part—can be rendered speechless or close to it.

I’ve never done that, though my father taught me the technique. I like my talking beasts, most of the time, and on occasion, I’ve had conversation with sphinx or lamia that were as close to talking with a person as could be.

After the marmoset incident, I left Bupus at home, the establishment the Duke allowed me, a fine place with stable and mews and even a heat-room, which the Ducal coal stores kept supplied all winter long and into the chilly Tabatian springs. I housed him in a stall that had been reinforced, and there were other animals to keep him company.

I’d gone to the circus to see their creatures. They had the crocodiles, which were nothing out of the ordinary, and the elephant, which was also unremarkable, since the Duchess kept two pygmy elephants in her menagerie. And an aging Hippogriff, a splendid creature even though its primaries had gone gray with age long ago. I was surprised to find his beak overgrown, as though no one had coped it in months.

“Look here,” I said to the man standing to watch the cages and make sure no one poked a finger through the bars and lost it. “Your Hippogriff is badly tended. See how he rubs his beak along the ground, how he feaks? Your tender is careless, sir.”

I was full of youth and indignation, but I softened when he perked up and said, “Can you tend them? We lost our fellow. How much would you charge?”

“No charge,” I said. “If you let me look over the hippogriff as thoroughly as I’d like to. I haven’t ever had the chance to get my hands on a live one.”

“Can you come back later, when we close up?” He looked apologetic. He was a pretty man, and his uniform made him even prettier.

“I can.” It’d mean a late night, but there was nothing going on that next morning—I could sleep in, and go to check the marmosets in the afternoon, or let the regular assistant do it, even, if I was feeling lazy.

So I came back late that night and pushed my way through the crowds eddying out, like a duck swimming against the current. He was waiting for me near the cages. I’d brought my bag of tools, and so we went from cage to cage.

He settled the Hippogriff when it bated at the sight of me, flapping its wings and rearing upward. It was easily calmed, and he ran his fingers through the silky feathers around its eyes, rubbing softly over the scaly cere, until its eyes half-lidded and it chirped with pleasure, nuzzling its head along his side.

I trimmed its beak and claws and checked it over before moving on to the other animals. It took me three hours, and even so, much of that was simply telling Rik what would need to be done later on—to stop giving the crocodiles sardines, for example, before they got sick from the oiliness.

I refused pay, and he insisted that he should buy me a cup of wine, at least. How inevitable was it that I would take this beautiful man home with me?

In the morning, I showed my household to my lover. The dueling marmosets, the brace of piskies, the cockatrice kept by itself, lest it strike out in its bad temper. And Bupus, sprawled out across the courtyard. Rik was enchanted.

“A Manticore!” he said. “I’ve never seen a tamed one. Or a wild one, for that matter. They come from the deserts in the land to the south, you know.”

A year later, diffidently, while the caravan was spending a month in Tabat, he mentioned to me that the Hippogriff had finally succumbed to old age and the caravan would like to buy Bupus.

I refused to sell, but when I married him, the Manticore came with me.

When the sun touched down on the horizon and lingered there, like a marble being rolled back and forth beneath one’s palm, we realized that there was some delay. If not tonight, though, they’d come tomorrow. Preddi and I discussed it all with shrugs and miming, agreeing to build a fire before the last of the sunlight vanished.

The woods that run beside the road there are dark and dangerous, which is why travelers stick to the road. As night had approached, there were no more passersby—everyone had found shelter where they could. Preddi and I would spread bedrolls beside the fire an

d keep watch in turns, but I wasn’t worried much. The smell of a Manticore keeps off most predators.

But as I picked through the limbs that lay like sutures across the ground’s interwoven needles, a crackling through the dry leaves at the clearing’s edge alerted me. Preddi was near the road, gathering more wood.

As I watched I saw stealthy movement. First one, then more, as though the shadows themselves were crawling towards me. As they emerged from the crevices beneath logs and the hollows of the trees, I saw a host of leprous, rotting rabbits, their fur blackened with drying blood, their eyes alight with foxfire. I did not know what malign force animated them, but it was clear it meant me no good.

Out of sight but not earshot, Bupus let out a simultaneous snore and long sonorous fart. Under other circumstances, it would have been funny, but now it only echoed flat and helpless as the rabbits, crouched as low to the ground as though they were snakes, writhed through the dry grasses towards me, their eyes gleaming with moon-touched luminescence.

The novelty of the sensation might have been what had me frozen. It was as though my belly were trying to crawl sideways, as though my bones had been stolen without my notice.

They were nearly to me, crawling in a sinuous motion, as though their flesh were liquid. Preddi wouldn’t hear me shout. Neither would the snoring Bupus. I strained to scream nonetheless. It seemed unreasonable not to.

And then behind me there was a noise.

A woman was coming towards me along the deer path, dressed in the onion-skin colored gown of a Palmer, carrying an ancient throwlight. It was made of bronze, and aluminum capped one end, while the other bulged with a glass lens.

She thumbed its side and it shed its cold and mechanical light across the leprous rabbits, which recoiled as though a single mass. They smoldered under the unnatural light, withered away into ringlets of oily smoke.

“I saw your fire from the road,” she said, letting the light play over the last of the rabbits. “This area is curse-ridden, and I thought you might not know to look out. Light kills them, though.”

Altered America

Altered America Carpe Glitter

Carpe Glitter If This Goes On

If This Goes On Fantasy Scroll Magazine Issue #4

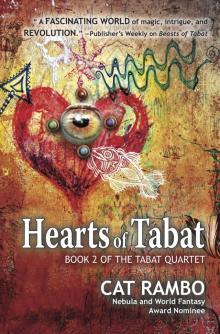

Fantasy Scroll Magazine Issue #4 Hearts of Tabat

Hearts of Tabat Beneath Ceaseless Skies #151

Beneath Ceaseless Skies #151 Clockwork Fairies

Clockwork Fairies Beneath Ceaseless Skies #170

Beneath Ceaseless Skies #170 Sugar

Sugar Near + Far

Near + Far Eyes Like Sky And Coal And Moonlight

Eyes Like Sky And Coal And Moonlight