Clockwork Fairies Read online

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

Clockwork Fairies

Mary the Irish girl let me in when I knocked at the door in my Sunday best, smelling of incense and evening fog. Gaslight flickered over the narrow hall. The mahogany banister’s curve gleamed with beeswax polish, and a rosewood hat rack and umbrella stand squatted to my left.

I nodded to Mary, taking off my top hat. Snuff and baking butter mingled with my own pomade to battle the smell of steel and sulfur from below.

“Don’t be startled, Mr. Claude, sir.”

Before I could speak further, a whir of creatures surrounded me.

At first I thought them hummingbirds or large dragonflies. One hung poised before my eyes in a flutter of metallic skin and isinglass wings. Delicate gears spun in the wrist of a pinioned hand holding a needle-sharp sword. Desiree had created another marvel. Clockwork fairies, bee-winged, glittering like tinsel. Who would have dreamed such things, let alone made them real? Only Desiree.

Mary chattered, “They’re hers. They won’t harm ye. Only burglars and the like.”

She swatted at one hovering too close, its hair floating like candy floss in the air. Mary had been with the Southland household for three years now and was inured to scientific marvels. “I’ll tell her ladyship yer here.”

She left. I eyed the fairies that hung in the air around me. Despite Mary’s assurance, I did not know what they would do if I stepped forward. I had never witnessed clockwork creations so capable of independent movement.

Footsteps sounded downstairs, coming closer. Desiree appeared in the doorway that led to her basement workshop. A pair of protective lenses dangled around her neck and she wore gloves. Not the dainty kidskin gloves of fashionable women, but thick pig leather, to shield her clever brown fingers from sparks. One hand clutched a brass oval studded with tiny buttons.

Desiree’s skin color made her almost as much an oddity in upper London society as the fairies. My intended. I smiled at her.

“Claude,” she said with evident pleasure.

She clicked the device in her hand and the fairies swirled away, disappearing to God knows where. “I’m almost done. I’ll meet you in the parlor in a few minutes. Go ahead and ring for tea.”

* * *

In the parlor, I took to the settee and looked around. As always, the room was immaculate, filled with well-dusted knickknacks. Butterflies fluttered under two bell jars on a charcoal-colored marble mantle with lilies of the valley carved into it. The room was well-composed: a sofa sat in graceful opposition to a pair of wing chairs. The only discordant note was the book shoved between two embroidered pillows on the closest chair’s maroon velvet. I picked it up. On the Origin Of Species, by Charles Darwin.

I frowned and set it back down. Only last week, my minister had spoken out against this very book. I should speak to Desiree. I knew better than to forbid her to read it, but I could warn her against discussing it in polite company or supporting he heretical notion that humans were related to animals, which contradicted God’s order, the Great Chain of Being.

Mary, the Irish girl, brought tea and sweet biscuits with a clatter of heels that were muted when she reached the parlor carpet. I poured myself a cup, sniffing. Lapsang Oolong. Desiree’s father, Lord Southland, was one of London’s notable titled eccentrics, but his staff had excellent taste in provisions.

The man himself appeared in the doorway. His silk waistcoat was patterned with golden bees, as fashionable as my own undulating Oriental serpents.

“Ah, Stone,” he said. He advanced to take a sesame-seed biscuit, eyebrows bristling with hoary disapproval behind guinea-sized lenses. “You’re here again.”

“I came to visit Desiree,” I replied, stressing the last word. I knew Lord Southland disapproved of me, although his antipathy puzzled me. If he hoped to marry off his mulatto daughter, I was his best prospect. Not many men were as free of prejudice as I was.

With his wife’s death, though, Southland had become irrational and taken up radical notions. So far Desiree had steered clear of them with my guidance, but I shuddered to think that she might become a Nonconformist or Suffragist. Still, I took care to be polite to Southland. If he cut Desiree from his will, the results would be disastrous.

“Of course he came to see me, Papa,” Desiree said from the other doorway. She had removed her leather apron, revealing a gay dress of pink cotton sprigged with strawberry blossoms. She perched a decorous distance from me and poured her own tea, adding a hearty amount of milk.

“I’ve come to nag you again, Des,” I teased.

A crease settled between her eyebrows. “Claude, is this about Lady Allsop’s ball again?”

I leaned forward to capture her hand, its color deep against my own pale skin. “Desiree, to be accepted in society, you must make an effort now and then. If you are a success it will reflect well on me. Appear at the ball as a kindness to me.”

She removed her fingers from mine, the crease between her eyebrows becoming more pronounced. “I have told you: I am not the sort of woman that goes to balls.”

“But you could be!” I told her. “Look at you, Desiree. You are as beautiful as any woman in London. A nonpareil. Dressed properly, you would take the city by storm.”

“We have been over this before,” she said. “I have no desire to expose myself to stares. My race makes me noteworthy, but it is not pleasant being a freak, Claude. Last week a child in the street wanted to rub my skin and see ‘if the dirt would come off.’ Can you not be happy with me as I am?”

“I am very happy with you as you are,” I said. I could hear a sullen touch in my voice, but my feelings were understandable. “But you could be so much more!”

She stood. “Come,” she said. “I will show you what I have been working on.”

There would be no arguing with her—I could tell by her tone—but a touch of sulkiness might wear her down. Lord Southland glared at me as I bowed to him, but neither of us spoke.

* * *

In the workshop, a clockwork fairy sprawled on the table. Using a magnifying glass, Desiree showed me its delicate works, the mica flakes pieced together to form its wings.

“Where did you get the idea?” I asked.

“In Devonshire, an old woman spoke of seeing fairies. There was an interview with her in Science-Gossip.”

I snorted. “Old women are given to fancies.”

Desiree shrugged, taking up a pick and using it to adjust the the paper-thin wing's hinge. “It made me think about how to create flying creatures. I chose to use bumblebees for my model, rather than the traditional butterfly wings. My fairies can resist strong winds and go where I wish them, according to the instructions I have laid into their ‘brains,’ which are based on the papers Babbage has published.”

Desiree is interested in such things, but I don’t find them nearly as engaging as spiritual matters. She droned on, but I cut her short. “Sometimes I think you don’t love me.”

She stopped. Her half-parted lips were like flower petals, an orchid’s inner workings. “Why do you say that?”

“You don’t understand my position,” I said. “As a dean, I must have a wife who is acceptable in society’s e

yes.”

“This is about the ball again,” she said. She reached out to touch my face, but I turned my head away and pretended to examine the articulated form half-assembled on the table near me.

“Very well,” she said. Her hand returned to her side. “If it means that much, I will go.”

* * *

That week fled pell-mell. I went to a lecture by John Henry Newman, and the theater to see How She Loves Him by Boucicault. I stopped by Lord Southland’s on three separate evenings, but most nights I dined at my club, on excellent quail prepared in the French style, or fresh haddock.

Desiree had started work on a mechanical cat. She took me into her workshop to look at it. A clockwork nightingale sang in the wicker cage hanging from the rafters, set in motion by our footsteps’ vibration.

“It’s still in the preliminary stages,” she said. A brass skeleton lay disassembled on the table, but it was laid out so I could see the cat-to-be’s shape. Mercury beads rolled in a white porcelain dish. A discarded spray of silver whiskers had been tossed in the coalscuttle.

I glanced around. “The deanery has a basement,” I said. “It houses our wine cellar and storerooms, but I have sent to have the front room cleaned and whitewashed for you.”

Desiree’s teeth flashed as she smiled. I stole a kiss and her breath smelled of licorice. I felt her skin’s warmth against my hands. True, the room was not as fine as this, but she would improvise and make do, for she was a clever girl. And once she had started bearing, such fancies would fall away. Her inventions, her clever machines, were simply a way to channel her maternal instinct. Once she had a child, she would find herself devoted to it.

While Desiree went upstairs to speak to her father, I lingered in the workshop. I amused myself by walking between the tables and shelves, examining her work.

I paused beside what looked like a dress form, a brass cylinder the size of a human torso. My cheeks flushed as I regarded it.

Shockingly, Desiree had given it the semblance of a maiden’s bosom, a suggestion of curves whose immodesty appalled me. Headless, armless, legless, the torso stood affixed to three steel rods that culminated in a circular base as wide as an elephant’s foot.

I reached out and touched its “shoulder,” then trailed my fingertips along the skin towards its chest. The oils from my fingers left a faint trail behind them, smudging the metal’s gleam. It was how corrosion started, I knew. Given time, would the stains grow to verdigris, show how intimately I had touched Desiree’s creation?

I buffed the marks away with a linen rag that lay on a nearby workbench. The stairs creaked beneath me in admonishment as I ascended to join Desiree and her father. They had been arguing again. I heard her father say, “Blasted pedantic popinjay!” and Desiree say, “Oh Father,” her tone coaxing and indulgent.

“You don’t have to settle for such a man!”

“If I want to be part of society and not an outcast, I need a proper husband! Claude and I will accommodate each other with time.”

That had an ominous sound, but we would discuss it later. They fell silent as I appeared. Southland’s face red with anger, Desiree’s smile as bland as her mechanical cat licking cream.

* * *

Everyone notable was present at Lady Allsop’s ball. Silks and satins gleamed like colored waters touched with flecks of light from cut gems. The air smelled of hothouse flowers and French perfume. The orchestra played as the dancers glided through a waltz.

I do not entirely approve of diversions like dancing, but society places demands on us. I was eager for the ton to place their benison on my bride to be. I would dance twice with Desiree when she arrived, but for the most part I intended to stay on the sidelines, drinking lemonade. Still, when a few partners pressed me, I gave in.

I know well that women find me alluring—no credit to anyone other than He who shaped me. But my calf shows to advantage in breeches, to the point where at least one too-bold miss had called it shapely.

And I knew very well that it was my looks that initially attracted Desiree. Like all women, she is drawn to this world’s baubles, not realizing their transient, mayfly nature. But with time, she had sounded my mind’s depths, and I flattered myself that what she found there had strengthened her attraction to me.

A woman I danced with mentioned that the Southlands had arrived. “Your fiancée, is she not?” she purred. “I saw her arrive with her papa, a half hour or so ago.”

I made my excuses and went outside the great hall to pass through the refreshment line, looking for Desiree. I caught sight of her ahead of me, in the side hall’s shadows, dark hair held up by an intricate mechanism atop her head. She paused beside a dusky silk curtain, speaking to a blonde, blue-eyed woman.

From the back I could see Desiree’s silk skirt: figured with gears, the teeth embroidered in red. I came up behind her and slid my hand through the crook of her elbow, drawing her close to show my pleasure at her presence there, despite her dress’s outré nature.

I realized my mistake from the way the woman pulled herself away. She turned and I saw her clearly, no longer Desiree. Her hair held brownish red highlights, and her eyes were an icy, outraged green. The patterned cogs were Michelmas daises, the teeth ragged petals, scarlet on cream.

I stammered apologies, backed away as quickly as I could, bowing.

I searched through the crowds for Desiree and failed to find her. I looked around the punchbowl, through a salon filled with young misses waiting to be asked to dance, their mothers hovering nearby. Desiree had never been among their ranks. Her father had been indulgent, allowed her to skip so many social niceties. I sought her amid the dancers and along the wall benches, where groups of men gossiped and women nattered amongst themselves.

I finally slipped outside into the starlit gardens. There I found her, scandalously alone with a man.

Pea gravel crunched under my boot heels as I approached, just in time to see him lean forward and take her hand. The night was cool on my outraged cheeks as I ran forward, pushing him away from her.

He staggered back, looking surprised. I had not seen him before: a dark Irishman with a narrow face and a nose like a knife blade. His black eyes were altogether too dark and romantic, like some hero in a novel.

Sometimes you dislike a man at first sight. As now. An expression that flashed over his face made me think he reciprocated the sentiment. He was, annoyingly enough, dressed impeccably, better than my own efforts, despite the Honiton lace at my throat.

Something wild in the cast of his features, the white flash of his throat, the enormous emerald on his hand, the way the moonlight glinted on his fingernails, made me think him something other than human, some besotted seraphim or an exotic nightmare borne of fever. A shiver worked its way down my back and spread its fingers to measure my ribs.

“Claude!” Desiree exclaimed, looking far from pleased at her rescue.

I ignored her, addressing the man. “You will not touch my fiancée again, sir. I am surprised at you, taking advantage of her in this fashion.” I did not say it, but my reproach was aimed at Desiree as well, even though I knew she could not know better in her foolish, naïve youth.

“Lord Tyndall brought me out here to discuss my designs,” Desiree retorted. “He had read the paper I published on the difficulties of shaping tungsten.”

I scoffed. “Indeed, he did his homework well so that he might lure you out here to compromise you.”

Unnervingly, the man smiled at me. “I had no idea the author of such an erudite work would turn out to be so charming, sir, but the pleasure was unexpected. Having finished with that conversation, I was merely offering to demonstrate the art of palm reading to your lady. I picked up some small expertise in it in my homeland.”

People were stirring in the nearest doorway, looking out to see what the loud conversation was about.

Tyndall spoke to Desiree. “I did not get the chance to tell you, lady: Your palm shows that you will take a long journey, soon.”<

br />

His accent was thick. It was ridiculous for an educated man to speak with such a heavy brogue, or to pretend to superstitious beliefs such as palmistry in order to lure women to him. But I stood down, not wishing to scandalize the gathering crowd.

Lady Allsop peered from near the back, the frown on her face threatening future invitations. I bowed and took Desiree’s arm, drawing it through my own. She resisted, then let me pull her into the house.

But she would not speak to me the rest of the evening despite the attendance I danced on her. In the carriage home, she relented, but only to upbraid me.

“I did as you asked,” she hissed at me, “and it was as painful as I imagined. But you were not even satisfied with that, and had to take away the one interesting conversation I was able to find.”

“Everyone loved you. How can you say such things?” I protested.

“Perhaps you were at a different ball than I,” she said. “Did you not see Lady Worth turn away lest she contaminate herself by speaking to a Negro? Or perhaps you did not overhear the sporting gentleman laying bets on what I would be like between the sheets?”

“Desiree!” I gasped, almost breathless at the shock of hearing such words from her innocent lips.

She turned away and did not speak to me again that night.

* * *

The next day I came to call, bringing chocolates and flowers and a pretty opal ring. Opals were her favorite gem. But she sent Mary to tell me she was feeling unwell.

I started to leave in high dudgeon, but Lord Southland called to me. He was in his library, or so he called it, a small room that smelled of pipe tobacco and old leather, so close that one could barely breathe. On the wall hung a portrait of Desiree’s mother by Robert Tait.

I studied it as he gathered his thoughts. I knew she had perished in childbirth along with Desiree’s younger brother, only a few years after Lord Southland had returned with her from a trip to America. No one knew exactly where she had come from, but common gossip maintained that she had been a slave escaped from the southern portion of that barbarous place, that she had lived with the Cherokee for several years before the young Southland, on tour, encountered her in New Orleans. She was beautiful, although in an exotic, unsettling way. Her dark hair hung to her waist, and the artist had chosen to paint it untamed, almost hiding her face behind it. Her dress’s satin was the color of a yellow rose just opening.

Altered America

Altered America Carpe Glitter

Carpe Glitter If This Goes On

If This Goes On Fantasy Scroll Magazine Issue #4

Fantasy Scroll Magazine Issue #4 Hearts of Tabat

Hearts of Tabat Beneath Ceaseless Skies #151

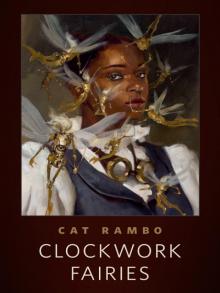

Beneath Ceaseless Skies #151 Clockwork Fairies

Clockwork Fairies Beneath Ceaseless Skies #170

Beneath Ceaseless Skies #170 Sugar

Sugar Near + Far

Near + Far Eyes Like Sky And Coal And Moonlight

Eyes Like Sky And Coal And Moonlight