Eyes Like Sky And Coal And Moonlight Read online

Eyes Like Sky

and Coal

and Moonlight

Stories by

Cat Rambo

This book is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any resemblance to real people or events is purely coincidental.

Table of Contents

Introduction to the Electronic Version

Eight Letters of Wonder, by Michael Livingston

Her Eyes Like Sky, And Coal, And Moonlight

The Accordion

I'll Gnaw Your Bones, the Manticore Said

Heart In A Box

In the Lesser Southern Isles

Up the Chimney

The Silent Familiar

Events at Fort Plentitude

Dew Drop Coffee Lounge

Narrative of a Beast's Life

Eagle-haunted Lake Sammamish

Sugar

A Key Decides Its Destiny

The Towering Monarch of His Mighty Race, Whose Like the World Will Never See Again

In Order to Conserve

Rare Pears and Greengages

A Twine of Flame

The Dead Girl's Wedding March

Worm Within

Magnificent Pigs

Grandmother's Road Trip

A Chronology of Tabat

Notes

Acknowledgements

Introduction to the Electronic Version

I'll tell you something, Dearest Reader. What you are viewing on your screen is an experiment of the highest order. It's an experiment I'm conducting due to my interest in the future of publishing.

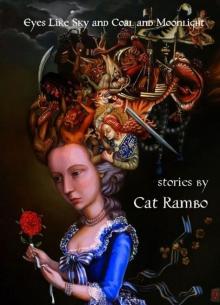

Paper Golem Press published the hardcopy version of this collection in 2009. At the time I signed the contract, I retained audio and electronic rights. The hard copy turned out beautifully, particularly with Mary Robinette Kowal's fabulous work in designing the book, including finding cover art that looked as though the artist, Carrie Ann Baade, had crawled around inside my head for a while and emerged with a frighteningly accurate rendition of the perils therein. Co-editors Michael Livingston and Lawrence Schoen worked hard at arranging the stories, making sure they flowed smoothly, eradicating mistakes, and generally doing a thousand things to make it better.

I was ecstatic to see the first copy when it arrived. I can't begin to say what a thrill it was to hold it in my hand.

But, like most humans, I'm rarely 100% satisfied. So I took the opportunity to change back a couple of decisions I didn't agree with, fix some typos along the way, and add a story that only appears in this edition. So what all is different?

For one, I'd originally written the story notes with an eye to them appearing after, rather than before, the stories, which led to a couple of spoilers here and there. So I've moved them back, and in some cases expanded on them.

Secondly, I've included the document we'd originally intended to use as an introduction, written by Jeff VanderMeer on the occasion of my appearance at Michigan-based (and wonderful, thank you guys so much for a great time) ConFusion.

Finally, I've added a story. Because I can. The story is "Grandmother's Road Trip," and it's dedicated to my grandmother, Nellie Warner McDonald.

Since the book's first appearance, several very nice people have said kind things about it, and it was an Endeavor Award finalist this year. I've sold some other stories, and written a few too. And now I've made my foray into e-publishing. Thank you for buying it.

All the best,

Cat

Eight Letters of Wonder

I’m not a gambling man. Never have been. But I bet the odds are good that I can guess what you, Dear Reader, are thinking as you hold this beautiful book in your hand. After all, almost everyone who encounters Cat Rambo’s work undergoes the same two-step process of thinking. I went through it myself several years ago.

If this is your first exposure to Cat’s work, you’re wondering if that’s her real name. There’s no chance, you’re thinking, that those two nouns actually came together in any natural way. One or both of the names just has to be fake, right? I thought the same thing once. But I was wrong. To quote the Seinfeldian response to a rather unrelated question of authenticity, “They’re real, and they’re spectacular.”

If, on the other hand, you’ve read Cat’s work before—any of it—then you’re thinking you know damn well what a good book this is going to be. And I’m pleased to say here at the outset that you’ll not be disappointed.

Cat’s career has been on a space-lift trajectory of late, and Rambo-reading veterans have no doubt why: Cat’s good. Really good. She moves smoothly in and out of genres and voices. Effortlessly, as if her work is the ether that binds them. Fantasy, science fiction, horror . . . Cat takes them on, two or three at a time, mixing and matching them with alchemically fantastic results. Jeff VanderMeer, introducing her as a recent Guest of Honor at ConFusion, called Cat’s fiction “often lyrical but tough-minded, unabashedly mixing traditional tropes with unconventional approaches. You get a sense in her work of someone who has actually lived a life and experienced a lot. That’s something you can’t really fake in fiction.”

As I said, she’s really good.

So good, in fact, that as I sit here staring at the table of contents for the amazing collection of her work that you and I, Dear Reader, are fortunate enough to hold in our hands, I wonder if Cat’s success was somehow fated, if somehow we have here, in the pages of this slender, precious volume, evidence of some fictional providence at work. Just look at that name again: Cat Rambo. It’s too striking to be legit—what with the cute purring-ness and the rough Stallone-ness juxtaposed in a violently abrupt eight-letter collision of worlds—yet it is. And more than just being real, it’s almost perfectly apt for the unique web that Cat’s fiction weaves. We are, after all, about to embark on a journey that takes us from memories of magic in strange lands to encounters with pirates, zombie girlfriends, famed elephants, distracted wizards, slave centaurs, and one of the most sweetly heartrending stories with pigs since Charlotte’s Web.

Cat Rambo. Colliding worlds in eight letters of wonder. It’s magical enough that it is so, more wondrous still that we get to share it. So let’s begin, shall we?

Michael Livingston, The Citadel

Her Eyes Like Sky,

and Coal, and Moonlight

The first time I saw Alkyone, her eyes were blue, the color of sky in a child’s story. The second time, her eyes were terrible coals, long past their fire. And the third, the third time—her eyes were moonlight, silvery as Lirathu’s benign gaze. That’s the color I remember best.

Almost a King’s Age ago, when I was just a girl, my parents ran an inn, the Blue Pipe. It sat just inside the city walls, serving travelers and merchants coming through Caravan Gate. Gone now, destroyed in the Rebuilding, but it stood through all the tumultuous years of my life: the night of the devastation, the battle between Kul and Isar, the long years of the Occupation.

Offering me some ale now to wet my throat? Very well. I like the dark brew, flavored with groundnuts. If you wish to hear of her, to know about the wind mage, Alkyone, it’ll quicken my tongue.

Smell the storm brewing this evening—that edge of lightning riding the wind? That’s how it smelled that first night they came. Everyone in the tavern was excited. Word had spread there was to be a secret meeting of those who opposed Lord Isar.

The commons were packed to the gills with Tan Muark and Tuluki followers of Kul. Everyone called him Kul, despite his rank, as high as that of Lord Isar. Everyone thought of him as a distinguished friend, an elder brother. The one who would defend us all.

In the back room, several of my siblings and cousins served a gathering too impor

tant to be seen. History being made, my brother Amos said, puffing himself up, by the Muark leaders and Kurac merchants, come to discuss what was to be done about the tyrant.

And elementalists. Does that shock you, nowadays when no one can admit to practicing the elemental magics? Even then, most people didn’t speak of it, as though it were something disgraceful. Sometimes I wondered about my father. He had a fiery temper, the way followers of Suk-Krath are rumored to, and once I thought I saw him light the fire in the hearth with a gesture, but I was very small at the time.

Alkyone was an air-mage. A hawk-faced woman who wore her white hair in tiny braids, each tied off with a stone bead, as though to weigh her down, keep her from flying off. Her left cheek was tattooed—a triangle of blue dots, set just below her paler-colored eye. I had never seen anyone like her before, and I pressed forward, staring, until she looked up and caught my gaze.

She smiled at me and shared her honey cakes, crumbling them with long, nervous fingers. Her accent was lilting as she told me she had never had honey cakes when she was growing up.

“I come from a village where the thornlands give way to the hills, in the east,” she said. “But most lately I am come from Allanak, child. Do you know it?”

Wonders came from the southern city of Allanak: obsidian bracelets, and puppets with joints carved from bone. And sticky dried insects laced with honey that came in big blocks so chunks could be pried off to be chopped and added to pastries. I said this.

She looked around at the press of people. “There were many people in Allanak, and then some, but still I am unused to being among such a crowd. I like the desert. I like sleeping where I can feel the wind on my face and hear what it sings, deep in the night.”

I ate a little honey cake and told her that usually we were not so busy.

“Do you know why everyone has crowded here?” she asked.

To fight Lord Isar, I said.

“And why we are fighting him?”

Her teacher’s manner made me impatient. I knew this lesson as well as she did. Two of my cousins and my brother Lucius had been taken by Lord Isar for speaking out against him, I told her.

She looked abashed. “Indeed. Down in Allanak I have been around those that do not understand the need to fight him, and so I have fallen in the habit of lecturing.” She held out the rest of the honey cake. “Am I forgiven?”

I accepted the cake. She smiled and leaned forward to sort through the bag at her feet. Smoke hazed the room, coming from pipes and the fireplace along the wall, and the air was damp with the smell of brandy and beer. People were still gathering, being stopped outside to give the word of the day, the word that signaled they were not one of Lord Isar’s spies. That night it was “the sun will shine again.” I have always remembered that.

Alkyone took out a box made of blue glass beads inlaid in larger squares. “These came from Allanak as well,” she said.

One of the men filling the room muscled his way through the crowd. He was blonde bearded, a northerner like me. As he approached, he scowled down at me, but spoke to her.

“What are you up to, Alkyone?” he said.

“Lightening my pack,” she said. “It has been heavy lately.”

“We can’t afford to be giving away things all over the place,” he said. “Come in the back room. They wish to know what our magics are capable of, and whether yours could carry someone outside the gate.”

I opened the box, and he spoke as I saw what lay inside. “Those are your favorite earrings, Alk!”

She put her head down, looking at the floor planks between her boot toes. “I had those before we ever met, Phaedrin. My friend Jhiran gave them to me, and I may give them where I will.”

That was the end of that. I said, “When you go back to your village—wouldn’t someone there want them?”

Her face shuttered tight enough to keep out wind or emotion. “They are all gone. I will not be returning.” She reached up to close my fingers over the earrings and smiled at me again. Then she stood and followed Phaedrin back to the crowded room filled with angry argument and low-voiced discussion.

I crept closer and listened. There was no chance of sleeping that night. I couldn’t understand everything that was said. But through the door I watched her talking, worrying her lower lip between her teeth as she thought before answering questions. Phaedrin watched her as though annoyed by the conversation, but the Muark, who never trust those outside their tribe, treated her as a comrade. It was something about her, something that shone through and made you want to be a little bit better, somehow.

Everyone left before the sun rose over the city. Alkyone’s group rode away to the south-east, down to Luirs and the Tan Muark lands, vanishing into the darkness of the North Road. After they had gone away, my cousin Liselle tried to get the earrings and the box from me, but coax and threaten as she might, I would not give them up.

“Keep your traitor-gifts then,” she said, taking a step back, face red with fury.

I didn’t know what she meant, but I knew it was bad. I pushed her down, and I hid the box and earrings in the stable-loft, where she couldn’t find them. Sometimes I took the earrings out and held them in my hand, and let them flash in the sun so the stable kittens could chase the bits of scattered light they threw across the ground.

Sometimes I pretended I was Alkyone, pretended so hard that it was as though I walked in a different skin. I would sit on the stone wall outside the inn and stare at the dust devils dancing in the road, willing them to move. My heart would leap when it would seem as though one had heard and answered. But then, inevitably, it would die away or move in a contradictory direction.

I wanted to be her, to have people listen to me instead of telling me what to do. I wanted them to smile at me as they did at her, with love and respect, and sometimes a trace of fear.

My ineffectual efforts at magic died out after a while and our lives continued. When I was twelve, there came rumors of magic outside the city. Travelers reported the undead walked the North Road at night, and no one dared journey beneath the moons. Day by day, the stories grew wilder. They said an ancient demon, the Lord of Ash, and his servants plagued Tuluk and that the Templarate could do nothing to stop him. Some said that the reason the Templarate did nothing was that they had given their power to Lord Isar.

My mother had been accustomed to using Isar’s name to threaten us when we misbehaved. Now she dared not invoke his name in threats lest she somehow come to his notice. At night we shuttered the windows and barred the doors, for fear of the sorts of travelers that might enter after the sun had set.

When I had my first woman’s blood, my mother said we would have a celebration, even though business was so bad. She braided my hair and pierced my ears and I wore Alkyone’s earrings, despite Liselle’s frowns.

The night winds were howling, and my mother lit thick cones of lanturin incense to keep away ghosts. In the middle of the meal—duskhorn steak, the wild-fed kind you can never get nowadays—the main door blew open, or so we thought at first. The youngest children were all screaming and things were confused. My mother glimpsed Alkyone’s form huddled outside, a few feet away from the lintel. My brothers pulled her in, dragged her beside the hearth, pressed hot tea and soup on her. She kept her eyes turned down, her cloak’s hood drawn up.

A few hours later, her friends arrived. They stood in the doorway. She did not look up. No one had wanted to go to bed after that, not with all the excitement, and my father had allowed us to heat watered wine and drink it, stretching out the sips to make our time awake as long as possible.

“Alk,” the leader said, his voice half-cracked with pain. He was a plain, brown-faced Northerner, the Kuraci. “Tell me it’s not true.”

“That what’s not true?” It was the first time she spoke that visit, and her voice was as sweet and intoxicating as the liquid in my mug. The wind outside changed pitch and tenor, softened, became melodic for a moment, a heartbeat.

He took a ste

p forward at the words, face brightening. “Then it’s not true—the Lord of Ash has not touched you?”

She raised her face slowly—I can see that clear as day in my mind’s eye, clearer than I see most things now—and the fabric fell away, revealing that her once-blue eyes were black as coals.

“See how he has touched me because I dared oppose him and his ally!” she said. “Like all his creatures, I’m marked. But is my spirit still my own? That I believe to be true, but I make no guarantees.” And with a bitter, brittle laugh, she pulled the hood back up around her face.

She did not look at them, but they looked at her. Five men, all from the crowd that had gathered to discuss Isar so long ago: the brown man, and Phaedrin, and a stocky little fellow, one of the kinless half-blood, and another man, thin but with the bleary reddened vision of a spice-smoker, and another of the Tan Muark.

“His evil lives in you—you are his servant now!” Phaedrin said, but the Tan Muark had a blade against his throat and backed him off, step by step. My littlest sister gasped and hid her face in my mother’s skirts.

“Could Kul cure her, perhaps?” the Muark asked.

“Perhaps, if he had the crown of Fel Karren—but no such luck yet.”

“What about Arianis?”

“You have not heard? Arianis is dead.”

Alkyone paled further. “Arianis gone? But he was the best of our leaders, our only guidance! No wonder the Lord of Ash stretched out his hand to take me so easily!”

She lowered her face into her hands and wept. And those men, they fell into silence and stood there looking at her in the way you would a stone that has become a scorpion, or a stick that writhes and becomes an adder.

When those black pits had been concealed by her long-fingered hands, I could move again. I put my mug down, and went forward to embrace her. I buried her head in my shoulder so I did not have to face that black gaze, but even so, I held her and did my best to conceal the terror that shook me, like an earthquake that sets the world ashiver.

Altered America

Altered America Carpe Glitter

Carpe Glitter If This Goes On

If This Goes On Fantasy Scroll Magazine Issue #4

Fantasy Scroll Magazine Issue #4 Hearts of Tabat

Hearts of Tabat Beneath Ceaseless Skies #151

Beneath Ceaseless Skies #151 Clockwork Fairies

Clockwork Fairies Beneath Ceaseless Skies #170

Beneath Ceaseless Skies #170 Sugar

Sugar Near + Far

Near + Far Eyes Like Sky And Coal And Moonlight

Eyes Like Sky And Coal And Moonlight